9/11 — the anniversary of Katherine’s cancer operation and her birthday — saw our roles reversed. This year, it was my turn to wear those flapping backless gowns and paper undies. She, ever patient and understanding, held my wimpy hand as I was prepped for surgery.

Meeting my near-neighbour, the anaesthetist, for the first time was a special surprise and gave the experience an unexpectedly intimate feel. We chatted about community and commuting as I drifted off. Spoiler alert: my end turned out alright — nothing sinister.

No doubt you remember exactly where you were on 9/11 in 2001, watching the grim attack unfold. A month before, I had a mediation at the World Trade Center. Over my many visits to NYC, my brother, a cousin, and I would often meet after work in a bar near the stock exchange. The tragedy held other personal connections too. My sister, who was then running a children’s hospital in Boston, spent months providing grief counselling to families, first responders, and especially the children.

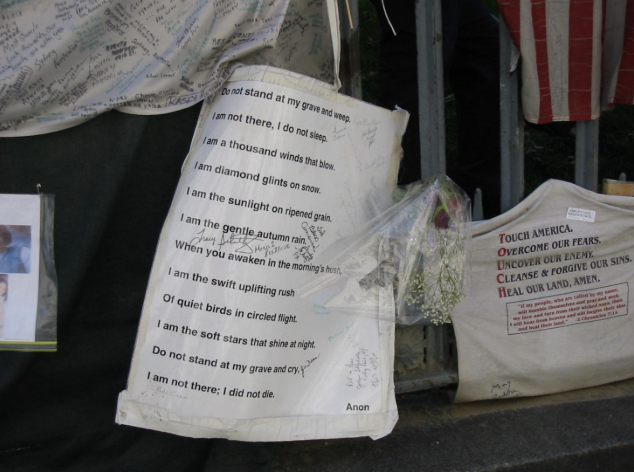

Amazingly, the little church and yard across the road from the plaza survived the explosions and became both a refuge and a shrine. I returned to New York later to finish the same insurance case and took photos of the site.

In recent years, especially during my recovery in November, I’ve often listened to a recording of Rabbi Irwin Kula chanting the final messages left for loved ones by those in the Twin Towers. These last cellphone conversations, from those who perished, are words from husbands to wives, mothers to daughters, and parents to children. In the dearness of their vanishing moments, not one of these conversations expressed anger or a desire for revenge. Instead, each simply and heroically witnessed a yearning to love, and the faith that love, ultimately, swallows up death.

I’ve rarely encountered anything as raw, devastating, and beautiful. I usually can’t make it through the whole recording.

The Rabbi set some of these sacred words to an ancient Jewish chant of the biblical book of Lamentations, which mourns the destruction of Jerusalem and the Holy Temple in the 6th century BCE. Jewish tradition is to chant the book once a year on the saddest day of the year, in the heat of summer. The book’s first word in Hebrew, Eicha, means “Alas, how?” It invites the community to reflect introspectively on how and why such destruction happens.

As states become sites of unfathomable brutality and hate, with some shouting in their certainty that we must “kill them all” and others just as certain in advocating for non-involvement, saying we should “let them kill each other,” compassion fatigue creeps in. We grow indifferent as superpowers hand their missiles and moral might to others, so long as the killing doesn’t happen in their backyard.

As these historical fault lines unravel at home and abroad, as old sabres rattle and the distant drums of war echo, and as old debates rage on, are we so angrily divided — politically, culturally, economically, racially, and psychologically — that even in Aotearoa, we seem to dislike each other? Could we care less about the struggles and pain of others?

Perhaps we should remember the lesson of those who were killed 23 years ago. We should reflect on the lives lost most recently and be humble in our certainties. For “Alas, how?” — the lament — can only be answered with one word: hope. Whatever our politics or views, we must do better at listening to each other and finding solutions that reflect respect across our differences.

As always, be gentle with yourselves and hold your loved ones close this holiday season.